If you go look at the Workman Publishing story about the passing of Peter Workman, you will notice something that all of us who ever had any contact with him already knew: Here was a person entirely connected to his work. His work happened to be heading an industry-defining publishing company for nearly half a century, but it was clear to me in the, oh, three minutes that I talked to him, that he was completely active in the process of publishing.

He clearly did not need to be. Workman Publishing was hugely successful from the minute he founded the company, publishing Yoga: 28-day Exercise Plan, which remains in print with sales that are still enviable. Other big successes were the "What to Expect" books for family planning and parental advice, and the "1000 Places to See" series of books. A third of Workman titles has sold more than 100,000 copies. No, the man who founded this company could have checked out long ago, claiming victory into a well-funded retirement.

Among those great successes was the invention of the tear-off daily calendar, the perfect pre-Internet medium for word-of-the-day, fact-of-the-day, cartoon-of-the-day, or the visually driven (and sure-fire hit, naturally) cat- or dog-of-the-day. These calendars, all produced with the Workman Publishing "Page-A-Day" brand, were a revelation in 1979, when the first of them began to hit the bookstore display tables around Christmas.

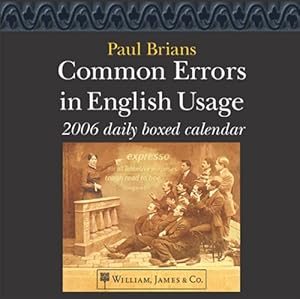

And that is where I come in. It's a little embarrassing to admit that I knew nothing of the history of these desk calendars when I had the idea to create one from Common Errors in English Usage. It seemed an ideal fit: not word-a-day but usage-point-a-day. And so, sometime in 2005 I developed the Common Errors in English Usage Page-A-Day calendar, filled with 365 pages of entries to be cycled through the course of 2006, each with its own page. We produced a very limited number of these, sort of a market test of 1000 copies. I was entirely ignorant of the fact that the most egregious error appeared right there on the box design and title page.

At some point I learned from a catalog company that would feature the calendar that the "Page-A-Day" label was actually a brand name owned by Workman Publishing. This was a problem. The artwork for the calendar had already been proofed and approved with the printer. Everything was in motion, and the motion needed to stop until this issue got resolved.

I put them on notice at the printer immediately. Fortunately, the calendar had not been produced, but unfortunately there would be delays for another round of proofs, and the schedule was too close for comfort already.

I decided to call Workman Publishing. I expected nothing noteworthy to come of this. Workman, I figured, is huge. It's corporate. I'm going to be tied up for three weeks with this mess, waiting for some legal assistant to get back to me. In short, I'm sunk. I was asking for something that seems silly in hindsight: permission to use the brand free-of-charge for an extremely small run of test-market calendars with the promise to cease and desist thereafter. In times like those, you just take your best shot and go for it.

I was in for a few surprises over the next couple of days. The first surprise was that when I called Workman Publishing, the person answering the phone knew exactly the company policy and had an authoritative answer for me right then and there. She listened to my story, though, and sympathized enough to give me some small hope that I might actually be able to proceed. This was late in the day, though, and she told me I'd have to wait to get a final, definitive answer after she had had a chance to talk to Peter about it.

"What?" I thought . . . talk to Peter about it? What about Legal? Isn't there going to be a Long Process of going through the copyright attorneys and Team of Experts for advice and consent? Hmmm . . . the only thing to do was the wait, and try to do so patiently.

I don't remember waiting long, though. I had to overnight a proof of the box and the title page for review, but it was not more than two days later that the phone rang in the office. The intercom beeped for me to pick up; Peter Workman was on the line.

This was getting surreal. I assumed, maybe, that this was a misunderstanding. Peter Workman could not possibly be calling me. Rather, this was Workman Publishing calling back, and not the actual Peter himself. I picked up the phone and gave one of those slightly garbled, nervous "hellos" you save up for when you meet people that are famous. Indeed, "This is Peter Workman" was the announcement I heard on the line. It was business, but there was no denying the underlying personality there, the charisma that sold a million copies.

I can't recount the whole conversation—I would just be making it up anyway. All I remember is that the answer was "No" to allowing any use of Page-A-Day for a non-Workman product, and that was A-OK with me. He gave bad news with the best of them. He said he needed to protect the brand, but that he understood very well the pickle that put me in. I figured he would know a thing or two about pickles, but there was also an element of "This is Peter Workman telling me I need to solve my publishing problem on my own," and coming directly from the man that was, well, inspiring.

The upshot of it is that the calendar was produced with the generic "Daily Boxed Calendar" label, and went on to appear in print for the next five years, largely with the help of Barnes & Noble, who even produced it with their own publishing imprint the final year that they had a calendar imprint. I worked with many great people there, but there was one huge difference with all the success of the calendar following that initial big flop: I could have never gotten on the phone with a Mr. Barnes or a Mr. Noble.

But don't take my word for it: read the comments at Workman Publishing to get a clearer picture of how engaged this publishing giant was. It spanned every minute of his career, not just the three spent on the phone with me to deliver some bad news in the best way possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment